Collection of cartographic data

Oppenheim’s interest in the provinces of the Ottoman Empire not infrequently led him to remote areas where no other European had yet been seen. The careful planning for these journeys and their course are documented by records of the team accompanying him which included secretaries, architects, photographers, Bedouin guides, and soldiers or gendarmes who were always armed to protect the caravan.

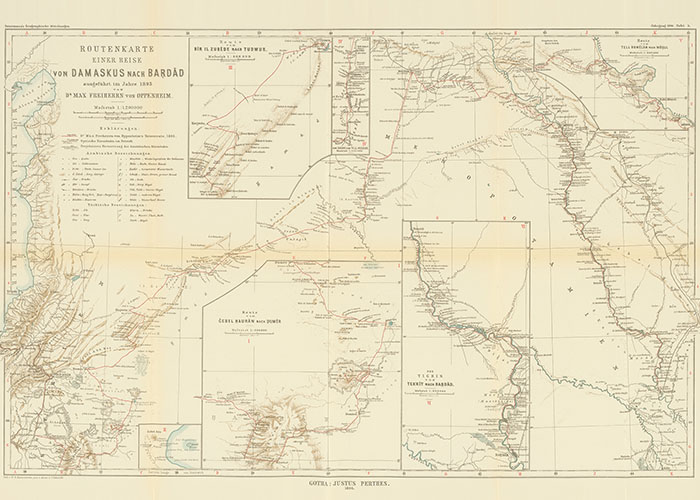

Photo: Research before departure, Arban 1912