Saving the Stone Monuments of the Tell Halaf Museum

The disastrous air raids of November 1943 severely damaged the exhibition space of the Tell Halaf Museum, along with the administrative building. The fire started by a phosphorous bomb destroyed many small finds, the monumental plaster reconstructions, and parts of the Islamic collection as well. All objects made of limestone were destroyed while the basalt sculptures experienced heavy damage.

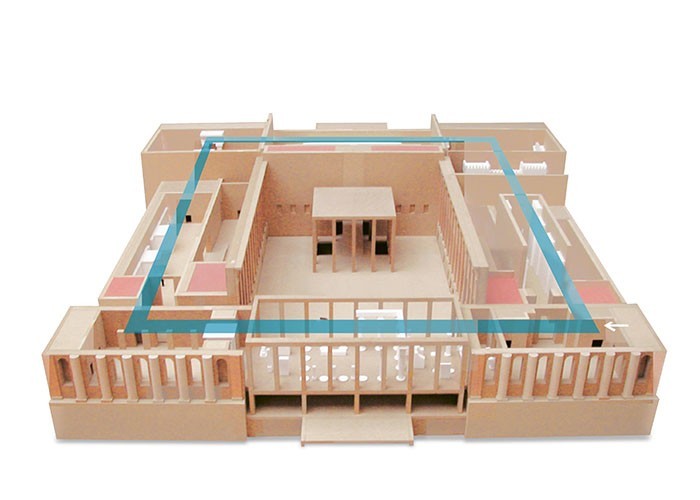

Photo: Remains of the stone monuments following the catastrophic fire in the basement of the Pergamon Museum, after 1944