Building Bridges between Orient and Occident: Max von Oppenheim (1860–1946)

Disparate facets and careers are hallmarks of Max von Oppenheim’s extraordinary life. He was a travelling scholar and adventurer, ethnologist and archaeologist, academic administrator and museum founder, active in politics and an engaged intermediary between the Orient and the West.

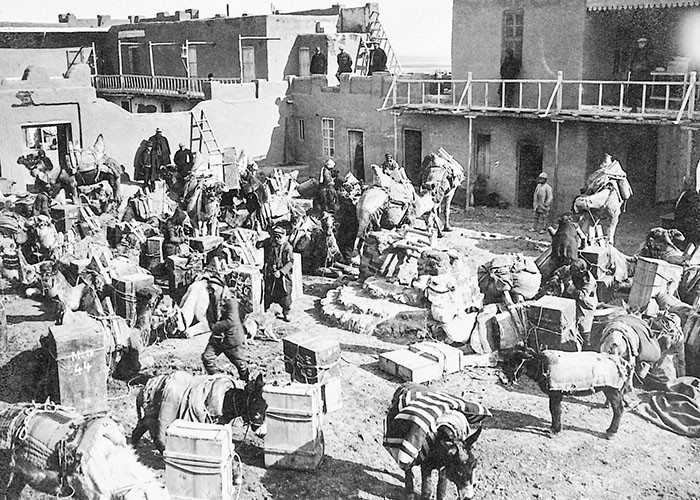

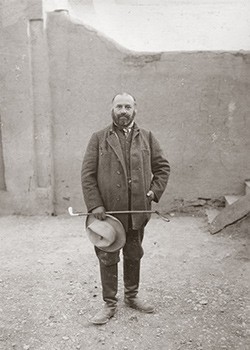

Photo: Max von Oppenheim in the courtyard of the excavation house, Tell Halaf 1912/13