The Manuscript Collection

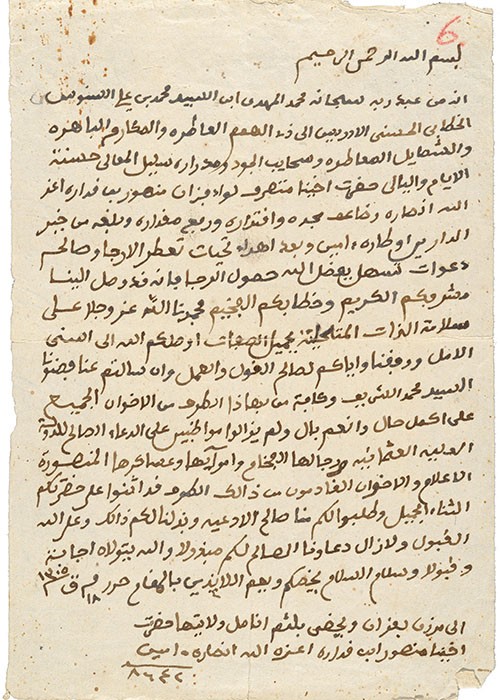

Max von Oppenheim stood in the tradition of collectors whose interest in Islamic manuscripts had originated in 17th century Europe. Travelers, diplomats, and colonial officials acquired treasures of Islamic literature which eventually formed the bases of many contemporary private and public libraries in Europe.

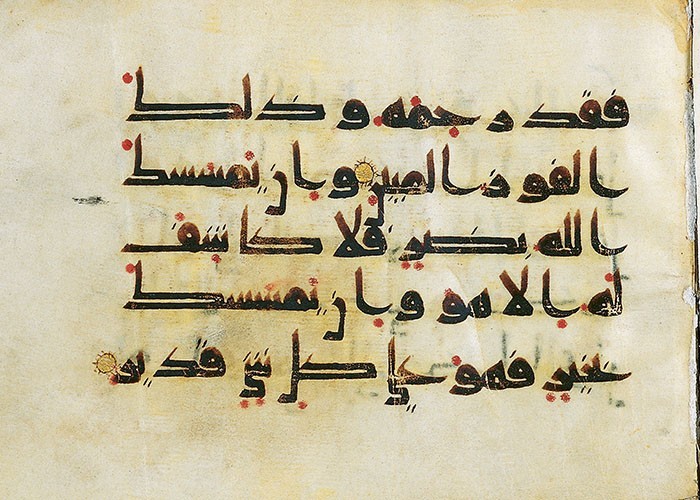

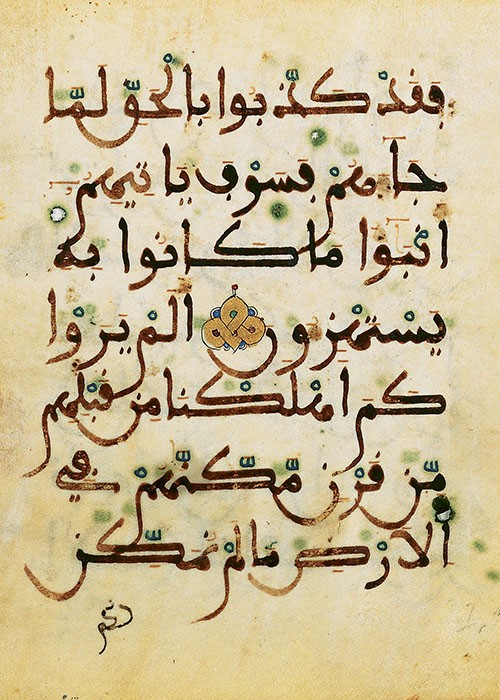

Photo: Parchment Koran fragment in Maghribi ductus, 12th–14th century